The genus Pinus represents the largest genus within the existing gymnosperms, encompassing over 100 species distributed across the northern hemisphere. It comprises the subgenera Pinus and Strobus. The subgenus Pinus is further divided into the sections Pinus and Trifoliae. Pinus species has spur shoots, with leaves bundled in a sheath. Classification within this genus is primarily based on the leaf count per sheath: the subgenus Strobus typically has five leaves per sheath, while the section Pinus has two, and the section Trifoliae has three. Additionally, the section Pinus is subdivided into the subsections Pinus and Pinaster.

In Japan, the subsection Pinus (of the subgenus Pinus) is represented by three species: Japanese Red Pine (P. densiflora Seib. & Zucc.), Japense Black Pine (P. thunbergii Parl.), and Ryukyu Pine (P. luchuensis Mayr.) (Fig. 1). Pinus luchuensis is endemic to Japan, with its distribution throughout the Nansei Islands, reaching its northern limit at the Tokara Islands. Similarly, P. thunbergii is endemic to Japan, with its presence in the southern Korean Peninsula believed to be the result of introductions from Japan over the past several centuries. Conversely, P. densiflora has a broad distribution across northeastern Asia, including the Japanese Archipelago.

Among the three species, P. thunbergii and P. luchuensis are close to each other. They form a clade with several species found in China and northern Vietnam, namely P. hwangshanensis W. Y. Hsia, P. tabuliformis Carr., P. densata Mast., P. kesiya Royle ex Gordon, and P. yunnanensis Franch. This clade is referred to as the “Pinus-thunbergii clade”.

The oldest known record of P. thunbergii dates back to the Pliocene era, approximately 3.2 million years ago, and was discovered in Tsunodu, Gotsu City, Shimane Prefecture, Japan. The only fossil record of P. luchuensis has been identified from the Pleistocene deposits, around 1 million years ago, in Nago City, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. Furthermore, P. mikii T. Yamada, M. Yamada & Tsukagoshi (Fig. 2) has been extensively reported from the Lower Miocene to the Lower Pleistocene across the Japanese Archipelago, with the exception of Hokkaido.

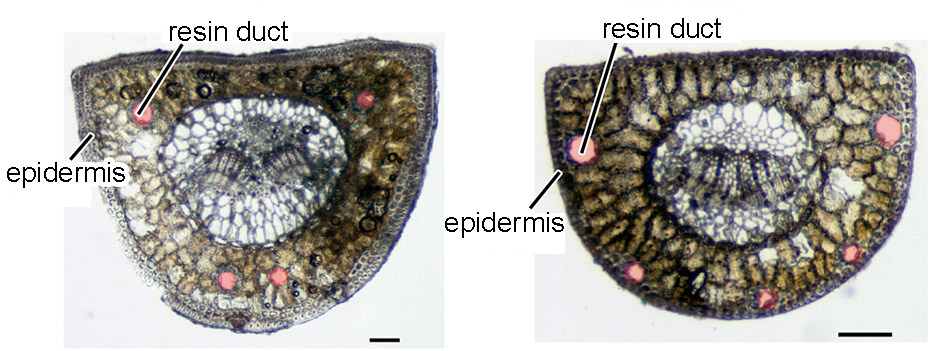

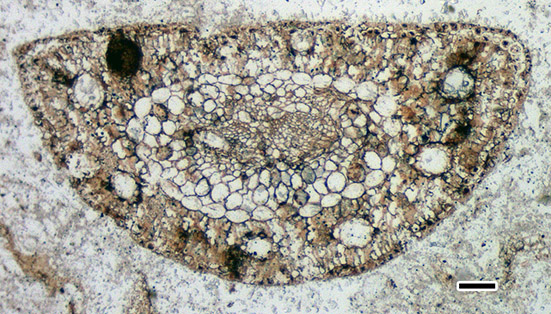

Species within the subsection Pinus can be classified based on leaf characteristics. For example, P. densiflora can be distinguished from species within the Pinus-thunbergii clade by examining the position of the resin ducts in a leaf cross-section: in P. densiflora, the resin ducts are in contact with the inner circumference of the epidermis, whereas in the Pinus-thunbergii clade, the resin ducts do not make contact with the epidermal cells (Fig. 3). Pinus mikii exhibits the resin duct characteristics associated with the latter group (Fig. 4), suggesting its phylogenetic position within the Pinus-thunbergii clade.

The cuticle covering the inner wall of guard cells occasionally develops a projection at both polar ends, known as a “polar extension.” Within the extant species of the P.-thunbergii clade, this feature is shared by P. hwangshanensis, P. thunbergii, and P. luchuensis. The cuticle of guard cells in Pinus mikii also exhibits this characteristic. Pinus hwangshanensis and P. thunbergii have longer and shorter polar extensions than P. mikii, respectively, while the length of the extension is nearly the same between P. luchuensis and P. mikii (Fig. 5). Additionally, the stomata are positioned closer to each other in P. luchuensis and P. mikii, but are separated by several epidermal cells in P. hwangshanensis and P. thunbergii (Fig. 5). These characteristics suggest that P. mikii is most closely related to P. luchuensis among the species of the P.-thunbergii clade.

Arrowheads indicate polar extensions. Scale bars, 50 μm.

Pinus mikii is the only fossil species of the P.-thunbergii clade found in Japan. Moreover, fossils of P. thunbergii have been discovered only in Japan. Considering these fossil records, we propose a hypothesis that P. luchuensis evolved from P. mikii through anagenesis, while P. thunbergii diverged from P. mikii through cladogenesis. Pinus mikii first appeared during the warmest period known as the mid-Miocene Climatic Optimum (MMCO), and P. luchuensis, a descendant of P. mikii, also prefers subtropical to warm temperate climates. The global temperature began to cool towards present from the end of the Middle Miocene (ca. 13 Ma). This climatic shift might have prompted some populations of P. mikii to migrate southward, from which P. luchuensis could have emerged. Conversely, P. thunbergii evolved from a population of P. mikii that adapted to cooler climates.

Some plant species that thrived during the MMCO may have survived the subsequent climatic cooling, potentially becoming the ancestors of the current flora of Japan. However, this possibility has not been explored in previous studies on the history of Japanese flora. The cases of P. luchuensis and P. thunbergii are the first to highlight this potential. More instances should be identifiable. Meanwhile, some Japanese plants may not withstand warmer climates because they have adapted to cooler conditions. These plants favoring cooler climates might face extinction if global temperatures continue to rise.